How is the Libyan Conflict Perceived by its Neighbours? Positions and Perspectives from the Maghreb

INSIGHT. Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia have different views on the Libyan conflict, reflecting their different priorities and objectives for the country.

Libyan context

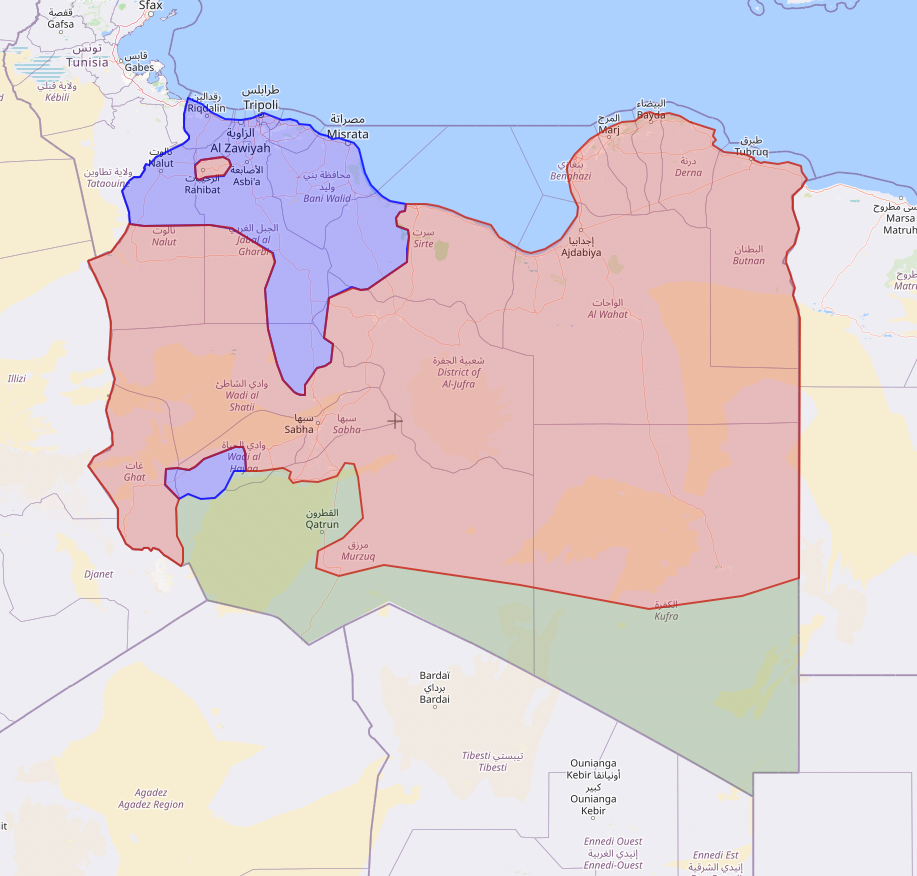

Since the fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, the Libyan state has experienced a prolonged period of political instability that has brought it to the brink of becoming a 'failed state'. The current cold standoff between the Government of National Unity (GNU)- which controls the west (in blue below) and is internationally recognised - and the Government of National Stability (GNS) - which maintains its own institutions in the east (in red below) and is backed by Marshal Khalifa Haftar's Libyan National Army - is preventing Libya from returning to the path of reconciliation and prosperity, despite its wealth of natural resources. The interference of third countries supporting one side or the other exacerbates tensions because of the multiple interests at stake. Thus, in addition to its important oil and gas fields, Libya occupies a privileged position in the central Mediterranean, is the gateway to the second largest migratory contingent to Europe, and is an essential crossroads between the Maghreb, the Mashreq and sub-Saharan Africa, so that control of the political transition could allow other countries to exert key influence in a strategic state in the current geopolitical context.

Morocco

After decades of ups and downs in bilateral relations, the lifting of international sanctions against the Gaddafi regime in 1999 allowed a degree of normality to return between Rabat and Tripoli. Moreover, the main stumbling block - Gaddafi's long-standing support for the Polisario Front - had diminished considerably as a result of the 1991 ceasefire and the evolution of the conflict in Western Sahara.

Following the overthrow of Gaddafi in the 2011 revolution, Rabat followed events closely, cautiously supporting the opposition and seeking to prevent the country's collapse and its contagion throughout the region. Thus, Morocco was one of the first countries to recognise the National Transitional Council (NTC), as part of its position of not opposing the demands and mobilisations of the Arab Spring on principle.

Morocco's role on the Libyan stage increased considerably following the agreements on the formation of the Government of National Accord (GNA), signed under the auspices of the UN in the Moroccan city of Skhirat in 2015. For Morocco, these constitute the legal framework for all its subsequent initiatives on Libya, including the inter-Libyan dialogue rounds in Bouznika and Tangier in 2020 and 2021. Thus, although Morocco was not invited to the Berlin International Conference in January 2020 (unlike Algeria), the so-called Rabat Compromise in December 2020 brought together the views of the House of Representatives and the High Council of State on the holding of elections, and it later participated in the Paris Conference in November 2021 at the invitation of France.

Morocco is making its efforts from a position of positive and active neutrality. Unlike Tunisia or Algeria, its lack of a common border with Libya allows it to adopt an intermediate position: it is sufficiently interested and involved in regional stability to try to mediate in the conflict, but it can do so from a prudent distance that gives it the appearance of impartiality. Moreover, its initiative and proactivity serve to present itself internationally as a provider of security in the region.

Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita sums up Morocco's official position since 2023 (the so-called Royal Approach) in four key points:

1. Morocco supports the national unity and territorial sovereignty of Libya and supports a solution within this framework.

2. The Kingdom also supports a peaceful solution to the crisis, far from any external interference and any initiative to impose military solutions. It therefore calls for the withdrawal of foreign mercenaries and the reintegration of militias into the regular army.

3. The solution to this crisis can only come through a Libyan solution (between Libyans) with international support, stressing the essential role of the UN in achieving a solution in this context.

4. The Kingdom distinguishes between the management of the transitional period and the question of legitimacy. The former must be agreed upon by the institutions that will work on the preparation of the elections, both the executive and the legislature. The question of legitimacy will be resolved through elections, and Morocco is continuing its efforts with the United Nations to find this solution.

On the basis of these principles, Rabat maintains excellent relations with the Tripoli-based GNU, which it explicitly recognises and with which it maintains fluid and friendly communications. Not surprisingly, in addition to the numerous meetings between the two foreign ministers, this recognition is such that, in November 2021, Libya renounced its candidature for the African Union Peace and Security Council in favour of Morocco for the period 2022-25, as a "response to Morocco's continued support for democratic elections in Libya". As a result of this agreement and the general improvement in the situation, the Moroccan consulate in Tripoli, which had been closed for years, was reopened in 2023.

On the other hand, while maintaining open channels of communication with the other parties, Rabat would in many ways be at odds with the Eastern GNS and Khalifa Haftar, not only for allowing foreign presence and Russian military support, but also for his penchant for Madjalism.

As part of his stated aim to support UN action, MFA Bourita met with UNSMIL chief Abdoulaye Bathily in 2023 and his interim successor Stephanie Koury in 2024, on both occasions reiterating the Kingdom's willingness to continue working with the UN mission within its mandate.

Recently, the Moroccan Foreign Minister also chaired a consultative meeting in Bouznika for members of the House of Representatives (based in the east) and the High Council of State (based in the west). Morocco thus intends to publicly commit itself to the 'Libyan-Libyan dialogue' within the framework of what it calls the 'spirit of Skhirat', referring to the 2015 agreements, so that Morocco maintains fixed positions that do not change with the events or contexts in relation to the Libyan dossier. Nevertheless, the move was criticised by the leadership of both sides and even the GNU's interim foreign minister, Taher Al-Baour, expressed surprise at the lack of prior coordination and the failure to follow the usual diplomatic channels, although he praised Morocco's efforts in the process.

Algeria

As Libya's neighbour, Algeria is particularly concerned about security, although the Libyan dossier is another element in the struggle with Morocco for political leadership in the region. Although it did not support the Gaddafi regime during the Arab Spring, it opposed international military intervention, believing that the resulting chaos would affect its national security.

On the security front, Algiers fears an increase in terrorist activity and the arrival of terrorists across their long shared border, as in the case of the 2013 attack on the Tinguentourine gas plant (40km from In Amenas). The Algerian government believes that although the terrorists have largely been defeated, they have not completely disappeared from southern and western Libya. Concerns about this aspect, as well as about arms trafficking, require Algeria to make significant military efforts and expenditures to defend and monitor its porous border.

Algeria has repeatedly reiterated its commitment to the stability and unity of this "brotherly country" and its support for efforts to promote an inter-Libyan consensus. It tries to present itself as a mediator and problem-solver in the region, with only moderate success so far. Although he participated in the Berlin 2020 Conference, he failed to gain the prominence he sought in the process. He then failed in his attempt to appoint his former foreign minister as head of UNSMIL, which was rejected by the Security Council on the grounds of a potential conflict of interest due to his proximity. However, some argue that this may have been due to the enmity between Algeria and the UAE (a non-permanent member of the Security Council at the time) following their disagreements on regional issues (such as the Western Sahara conflict or the Abraham Accords) and Abu Dhabi's support for Marshal Haftar.

In August 2024, during a meeting of the UN Security Council, the Algerian representative presented the 3 basic points of his position:

1. The solution to the Libyan crisis must be peaceful and political.

2. The solution requires a inter-Libyan process under the tutelage of United Nations.

3. The solution must lead to free, fair and transparent elections that bring together all factions of the Libyan people, guarantee the unification of institutions and respond to their aspirations both internally and externally.

In sum, Algeria's Permanent Representative to the UN, Amar Bendjama, told International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Karim Khan's biannual briefing on Libya that Algeria's position is based on three principles: 'the inviolability of justice, Libya's sovereignty and the need for regional stability'.

Algeria is therefore promoting an inter-Libyan dialogue to resolve the crisis, involving all factions, including the Muslim Brotherhood, which Marshal Haftar considers to be terrorists (as do the UAE and Egypt).

In these efforts, the country maintains a close relationship with the GNU, with whose institutions has met on several occasions in recent years. Indeed, last October president Abdelmajid Tebboune met in Algiers with his counterpart from the Libyan Presidential Council, Mohamed Al Menfi, with whom he said he was in "full agreement on all the issues" discussed, especially the need to hold elections after more than a decade of political crisis. According to previous statements by current MFA Attaf, Algeria believes in the "vital and decisive nature of the elections".

On the other hand, it has maintained a position of animosity towards Marshal Haftar, whom the Algerian government considers a proxy of foreign powers (France, Egypt, UAE) whose interests are contrary to Algeria's, and an element that has disrupted Algeria's efforts to de-escalate the situation in Libya. Unsurprisingly, former MFA Boukadoum visited the east in 2020 but was unable to meet with Haftar.

Tunisia

Tunisia also recognises the GNU, although it has several points of disagreement. For years, its "state-to-state" foreign policy meant that it had no relations or communication with the other parties, which was criticised for a lack of neutrality. However, since President Kais Saïed came to power, the country has adopted a policy of active neutrality and a more proactive and pragmatic diplomacy. For example, there have been frequent contacts with the GNU over the past year and a half, including several communications between Saïed and Prime Minister Aldelhamid Dbeibah or President of the Presidential Council Al Menfi.

The Tunisian government is strongly opposed to foreign intervention in the Libyan conflict and, in this sense, rejected the Turkish request to use Tunisian territory to provide military support to the GNU when attacked by Haftar’s forces. Tunisia has been a focal point in the Libyan crisis, serving as a base for humanitarian contingents or UNSMIL itself, and the main Western embassies in Libya have been based in Tunis for years. The country has therefore hosted many institutional meetings and dialogue rounds in the context of the work of the UN and the powers involved in the process. For example, UNSMIL Acting Head of Mission Stephanie Koury met with Foreign Minister Mohamed Nafti in the Tunisian capital in September, where he reiterated his government's willingness to contribute to the UN-led dialogue and reconciliation efforts.

Tunisia's main concern is also security. More than a million Libyans crossed the border after the Arab Spring and most are still there. President Saied attaches great importance to the migration issue, and last year there were several incidents at the border, after which the Libyan press accused Tunisia of expelling hundreds of migrants to the Ras Jedir border area, leaving them to their fate in the desert. On 9 August, the two countries signed an agreement on the distribution of irregular migrants at the border. This month, Tunisia overtook Libya as the first port of call for migrants heading for Europe (20,000 people in July). In addition to the worrying migration issue, Tunisia fears that instability in Libya will allow the transit of terrorists and organised crime networks across their long common border.

A minor incident over border demarcation also occurred in November last year, when Tunisian Defence Minister Khaled al-Suhaili declared that his country 'will not allow an inch of national territory to be neglected' and told parliament that the issue of border demarcation and surveillance with Libya was being negotiated between the two countries. The Libyan Foreign Ministry of the GNU, on the other hand, stated shortly afterwards that the border demarcation 'has been settled and is not subject to discussion or reconsideration'. The controversy also involved the Libyan parliament in the east of the country, which condemned the Tunisian defence minister's statements and warned of the danger of damaging the borders with Tunisia.

The other big issue is economic. Over the past five years, trade between the two countries has grown by 46.9 per cent, and by 10.8 per cent in the past two years, exceeding $1 billion a year for the first time. Both governments have set a target of reaching $1.7 billion a year in the medium term. Of particular note is the initiative to create a Tunisia-Libya continental trade corridor to sub-Saharan countries, with the aim of developing the Ras Jedir border area and integrating it into the African Continental Free Trade Area (ZLECAF). The Ras Jedir border crossing was opened last July following an agreement between both governments, but the Mashhad Saleh border crossing remains closed, affecting trade between the two countries. On 24 September 2024, the Minister of Economy and Trade, Mohamed Al-Hweij, met with the Tunisian Ambassador to Libya, Asaad Al-Ajili, to discuss improving economic cooperation between the two countries by improving common land borders and streamlining procedures for the movement of goods and services.

In April 2024, Tunisia hosted an Algeria-Tunisia-Libya meeting as a 'consultative meeting between these brotherly countries' on the Maghreb, to which neither Morocco nor Mauritania were invited, with the aim of 'unifying positions' to face the various international crises. Then, on 29 September, several business organisations, political leaders and private companies met at the 6th annual Tunisia-Libya-Algeria investment forum to promote the opening of markets and improve trade figures. The creation of a new shipping line between the town of Zarzis in south-eastern Tunisia and Tripoli, the capital of Libya, was also proposed. Direct flights have also been proposed between Djerba airport (Tunis) and various destinations in Libya and Algeria.

Mauritania

Mauritania also maintains full diplomatic relations with the GNU in Tripoli. In early October, President Mohamed Ould Gazhouani, accompanied by AU Commission President Moussa Faki and Congo's Foreign Minister Jean-Claude Gakosso, visited Libya, and the delegation met in Tripoli with GNU Prime Minister Dbeibah, who described the visit as "a strong message of support for Libya at this critical time". The Mauritanian President said that Libya's stability will be reflected on the African continent as a whole and that the AU is committed to continue supporting Libya to achieve national reconciliation and sustainable development, adding that it is essential for Libya to regain its natural role within the Union.

On the same visit, however, the Eastern GNS refused to receive the delegation, apparently in response to an earlier Mauritanian rejection of a request by Prime Minister Osama Hammad. During a visit to Mauritania described as 'controversial', Hammad asked for access to Libyan assets frozen in the country, including his stake in the Chinguitty Bank (a subsidiary of the Libyan Foreign Bank). In return, according to the same source, Hammad offered Nouakchott "the possibility of working with Wagner's forces, which occasionally enter Mauritanian territory and are accused of harbouring Malian rebel leaders".

Conclusions & Foresight

All the Maghreb countries are concerned about the evolution of the Libyan conflict and, in practice, show an interest in the success of the stabilisation and reunification process, which would clearly have an impact on the stability of the entire region.

For Algeria and Tunisia, however, the resolution of the conflict is more urgent, as they are particularly concerned about the security aspect. Algeria fears that its long, porous borders will allow the entry of criminals and terrorists and a repeat of the 2013 attacks, while Tunisia wants to stem the haemorrhage of migrants coming from or crossing Libya in search of a new gateway to Europe.

Morocco has no common border, so where it has the most to gain is on the reputational front. It wants to be seen as a regional leader committed to stability and able to influence and mediate between parties. In this way, it gains support for its own political claims (e.g. Western Sahara) by presenting itself as a moderate and responsible state in the international sphere. And it gains access to a substantial source of oil and gas.

On its hand, Mauritania would have no particular interest in resolving the dispute one way or the other. Certainly, Libya's instability may allow it to present itself as a stable country in front of its Western partners, and so it seems that it will limit itself to keeping pace with its neighbours Algeria and Morocco by supporting the GNU from the West, in its well-considered strategy of equidistance practiced in recent years.

However, a strong Libya on the international stage may not be of much interest to its Maghreb neighbours. Libya is a major source of oil and gas and could become an uncomfortable competitor on the markets, especially thanks to its historic relations with Italy, to which it is linked by a gas pipeline and whose government is doing its utmost to strengthen this friendship by multiplying its contacts with all parties.

It should not be forgotten that before the fall of Gaddafi, despite international sanctions until the end of the century, Libya was one of the economic powers of Africa (and therefore of the Maghreb) and that its relations with its neighbours were not always friendly (and not only because of the personality of the leader). A stable and powerful Libya could therefore once again become a key player in the struggle for regional and Mediterranean leadership.

What is certain, however, is that the Maghreb countries, even if they have some influence on the conflict, are unlikely to play a decisive role in its resolution and will therefore have to dance to the tune of other stronger powers such as the EU, Egypt, Turkey, the UAE and Russia, all of which having key interests in the country and on which it will ultimately depend whether Libya perpetuates instability and chaos or, on the contrary, embarks on the path of peace and unity.