What is Happening in Western Sahara?

INSIGHT. Keys to understanding a conflict that seems to be reopening after the latest clashes in the demilitarised zone of El Guerguerat.

Western Sahara is still considered by the UN as a "non-self-governing territory to be decolonised", decades after being administered by Spain as a colony since the Berlin Conference of 1885 and later even as a province (between 1958 and 1976).

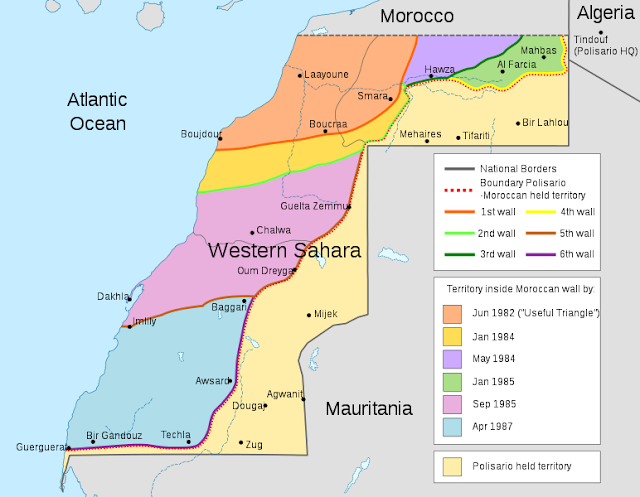

After the so-called Green March led by Morocco and the signing of the Madrid Tripartite Agreement (Spain, Morocco and Mauritania) in 1975, Spain abandoned Western Sahara without legally ceding its sovereignty, as the UN declared the agreement to be contrary to international law. This immediately triggered a conflict between the Sahrawi Polisario Front (militarily supported by Algeria and Libya) and its neighbours, who had divided up the territory left by Spain. Although Mauritania withdrew in 1979, leaving the area to the Polisario and its self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), hostilities with Morocco continued until 1991, when a ceasefire was signed under the auspices of the UN, which appointed a peace mission (MINURSO) to ensure it was maintained and to establish the conditions for a referendum in which the Sahrawi people would decide their future.

Since then, however, no referendum has been held, Morocco controls the western or oceanic part which includes important cities such as Laayoune and Dakhla and has built a wall (in red, in the image) almost 3,000 km long to separate it from the territories administered by SADR.

During the conflict, a large part of the Sahrawi population (between 90,000 and 200,000 people, according to sources such as the UNHCR, although the number is still under debate) was forced to take refuge in the Tindouf camps in Algeria, where it remains, awaiting a definitive solution.

Trigger

The tension began on Friday 13 November when the Moroccan army entered the demilitarised zone south of El Guerguerat, which consists of an uninhabited desert strip (considered a "buffer zone") of about five kilometres that separates the border post established by Morocco (without international recognition) to the north from the border with Mauritania to the south.

For years, this strip has been crossed by numerous trucks and vehicles carrying goods between Morocco and Mauritania, against the protests from the Polisario Front, which considers it a violation of the peace agreements. It is no coincidence that since the end of October a group of between thirty and fifty Sahrawians have been blocking the route, which apparently triggered the Moroccan army's action to evict them, under the declared intention of unblocking commercial traffic.

This manoeuvre was responded to by the Polisario, leading to exchanges of fire which, according to some sources, did not cause casualties but provoked a declaration of war by the Polisario Front. SADR has so far issued twelve 'war reports', in which it claims that its Sahrawi People's Liberation Army (SPLA) has attacked several Moroccan bases or observation posts on the other side of the wall. However, Morocco only acknowledges having suffered fire attacks in El Guerguerat and Mahbes, in both cases - it claims - responded to by the Royal Armed Forces.

Underlying causes

After the last few years of relative stability, and another blockade attempt in El Guerguerat in 2017, these new clashes found their roots in the very long time that has elapsed since the holding of a referendum to allow the Sahrawi people to decide was proposed as a means of resolution.

Indeed, much of the unrest caused by the conflict is to be found in a Sahrawi civil society - especially the youngest - that is deeply dissatisfied with the stalemate in which the conflict finds itself. After almost thirty years stuck in the Tindouf refugee camps waiting for a promised referendum that never comes, the Sahrawians intend to increase the visibility of the conflict and force the UN and the international community to reach a definitive solution, after suffering the rejection of their claims in recent years. In this scenario, the fisheries agreement between Morocco and the EU affecting Sahrawi fishing grounds has not been stopped, nor has Rabat's phosphate exploitation been halted despite its legal disputes. Moreover, discontent among some of the refugees has resulted in the emergence, earlier this year, of the 'Sahrawis for Peace' Movement as a political alternative to the Polisario Front. Finally, must be taken into account the threat posed to the region by terrorism and the risk that many young people, faced with the grim prospect of remaining in the refugee camps sine die, may join the ranks of the terrorist organisations that are spreading throughout the Sahel region.

For Morocco, the Western Saharan territories are of enormous strategic value, as they are the only land exit to the rest of Africa (the border with Algeria has been closed for years), as well as an important mining centre (mainly phosphates, essential for Rabat's finances) and a crucial fishing bank that allows it to negotiate substantial trade agreements with the EU. Asphalting the stretch of the El Guerguerat strip, thus completing the work started in 2017, is of vital importance for Moroccan trade with Mauritania and the rest of the Sahel. Hundreds of trucks pass through this route every day, employing more than an hour to cross the barely five kilometres of road. For these reasons, Morocco prefers to keep a low profile in the confrontations with the Polisario, as it knows that time is on its side and that keeping the conflict out of the international media spotlight would allow it to continue exploiting the territory as it has done so far.

MINURSO

The 'United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara' was established in 1991 to observe the ceasefire and organise a referendum on self-determination for the Sahrawi people. Since then, its mandate has been successively extended for annual or six-monthly periods.

However, the organisation of the referendum - initially scheduled for February 1992 - has been hampered and eternally postponed by the difficulty of drawing up a voter register, given the conflicting positions of the two sides: on the one hand, Polisario argues that only those who lived in the area in 1974 and their descendants can vote, while Morocco advocates the inclusion in the register of the population that has moved to the territory since then (today being a majority). This led, among other things, to the resignation of Special Envoy James Baker in 2004, after several unsuccessful proposals for a solution.

The UN Secretary-General's latest report to the Security Council, dated 23 September this year, already highlighted some ceasefire violations by both sides. Despite acknowledging his delay in appointing a replacement for the previous Special Envoy (former German President Horst Köhler, who resigned in mid-2019 for health reasons), Secretary-General Antonio Guterres (who is familiar with the conflict, having visited the refugee camps when he was High Commissioner for Refugees) had already expressed in that report his concern about the setback in compliance with the 1991 Agreement, due to the incursions by both sides into the El Guerguerat security strip.

In any case, it is particularly significant that in its latest resolutions the UN has ceased to speak of the referendum as its main objective, and today advocates "finding a just, lasting and mutually acceptable political solution that will provide for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara", with ambiguous terms such as "political process" or "political solution" being frequently used instead.

International reactions

There is a strong imbalance between the contenders in terms of their respective international backing.

On the one hand, Morocco has the support of a large number of countries in the dispute. Thus, although no country has yet recognised its sovereignty over the annexed territories, as many as 16 countries have established consulates general in El Aaiún - most recently the United Arab Emirates - in what constitutes implicit and symbolic support for its claim. Other countries such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Jordan, as well as regional organisations such as the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab Parliament, have explicitly expressed their support in the aftermath of the clashes. Morocco's efforts to weave an international network of support for its demands in recent years, especially since its return to the African Union in 2017, therefore seem to have been successful.

As for the SADR, despite having been officially recognised by many countries (up to 54 in 2002, according to the European Parliament) and being a full member of the African Union, it has few allies for its demands. Libya's withdrawal of support in 1984 left Algeria as its only formal ally in the region. However, despite its high war potential, Algiers is opposed to the escalation of hostilities and has urged both sides to exercise restraint. Not surprisingly, the country is still in a volatile situation following the recent approval of the constitution by referendum in early November (which still needs to be endorsed by President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who is hospitalised in Berlin).

Mauritania, the other signatory to the 1975 Tripartite Agreement, also calls for calm and urges the contenders to "exercise restraint" and "maintain the ceasefire and seek an urgent consensual solution to the crisis".

In Spain, despite its status as a former colonising power, the attitude of successive democratic governments has been one of apparent neutrality and respect for the political process sponsored by the United Nations. Not surprisingly, there have been hardly any official statements on the matter in recent days, beyond the communiqué from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which reproduces the terms of Secretary General Guterres' report, and "urges the parties to resume the negotiating process and to move towards a just, lasting and mutually acceptable political solution". Home Affairs Minister Fernando Grande Marlaska met with his counterpart in Morocco this week to discuss the recent flood of migrants received in Gran Canaria, although the official communiqué of that meeting contains no reference to the clashes in El Guerguerat, and in subsequent statements he has again limited himself to invoking the reference to a "fair and acceptable solution".

Prospective

Javier Otazu has accurately described this conflict in La Vanguardia as the "battle of the narrative", i.e. a situation in which, due to the limited presence of observers or the international press, each contending party conveys to public opinion the information that most favors its interests. Thus, in contrast to the Polisario Front's almost daily war reports of armed attacks on the Moroccan side, Rabat denies having suffered any damage. While the Polisario claims that the actions of the Moroccan army against the demonstrators blocking the El Guerguerat crossing were the most serious, official Moroccan sources argue that it was merely a peaceful operation of eviction and restoration of commercial traffic in the area, an action that is best defended in international circles and which has so far led most countries to call for restraint on both sides.

It seems logical to deduce that the Sahrawi population will try to gain visibility and mobilise international reaction to a dispute that has been dragging on for too long. Faced with a referendum that never comes and a situation of paralysis in the refugee camps with no prospect of change, Sahrawi youth want to give new impetus to the issue, although it does not seem that this confrontation will mobilise international public opinion, which is currently much more concerned with other matters, as has been made clear by the limited media coverage given to the clash.

For its part, Morocco will limit itself to progressively lowering the tone of the confrontation and trying to calm the waters as soon as possible. It is well aware that time is on the side of its 2007 autonomy proposal for the territory under Rabat's administration, for even if the referendum were to be held, it would probably be in its favour if the population arriving after 1976 were finally included in the census. This is why the Moroccan ambassador to the UN has ruled out that his country will go to war with the Polisario Front, although he claims to be "ready to defend civilians, to defend its territory and its territorial integrity".

Most observers therefore rule out more serious clashes in the short term, not only because of Morocco's unwillingness, but also because of the strong imbalance of forces between the two sides, which could only be altered in the event of outside intervention. However, it does not appear that Algeria (Polisario's main backer) wants an open confrontation, as Algiers has already called for containment and de-escalation.

Consequently, it does not appear that the current events in El Guerguerat will trigger a definitive solution to the conflict, at least in the short to medium term, so that the dispute will continue to stall until the circumstances and context (involvement of the UN or other actors) are altered in some way.